By Benjamin Ouedraogo

If I had to photograph a cultural event, I would definitely choose the Dakar Biennale,

known as Dak’Art. It’s not just an artistic event. It is a real breath, an effervescence that

crosses the whole city, transforms its walls, its streets, its looks. Photographing the

Biennale would be trying to capture the heartbeat of contemporary African art in one of

its most vibrant epicenters.

A sensitive and contextual approach

I would not rush, camera in hand, into showrooms or crowded openings. I would arrive in Dakar a few days before the official opening. I would go for a walk in the districts of Medina, Yoff, Ouakam. I would sit in a cafe to listen to conversations, I would talk to art students, artisans, street vendors. I would like to feel what the Biennale triggers in bodies and minds. My photographic approach would then be guided by what is transformed, what vibrates in the off-field: the backstage, the installation gestures, the curious looks of passers-by.

What I would try to capture

I would not try to document everything. I would rather aim for a series of significant fragments. First, the artists at work: their concentration, their hesitations, their solitude sometimes. Then interactions: children who marvel at an installation made of recycled materials; passers-by who stop in front of a mural; visitors who debate in front of a confusing work. I would also pay attention to details: a hand that draws a line of paint, a shadow cast on a sculpture, an ephemeral graffiti on a white wall.

I would like to photograph art as a living process, in perpetual metamorphosis. For this, I would favor natural light, the wide framing that lets the space breathe, but also the close-ups that reveal the material, the texture, the gesture.

Why the Dakar Biennale?

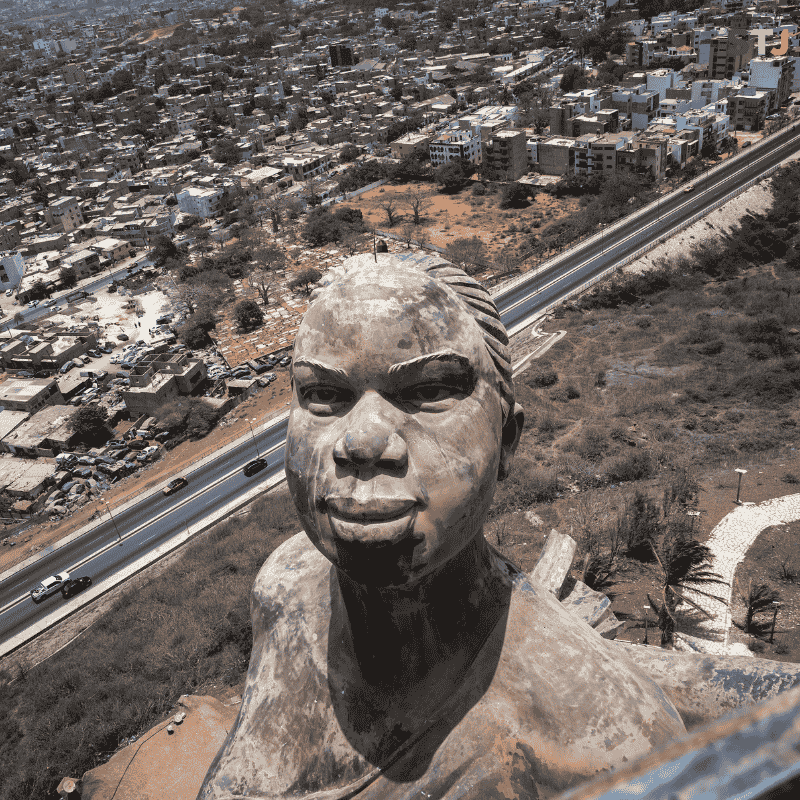

Because it’s much more than an exhibition. “Dak’Art is a party” according to Africa magazine. Since its creation in 1990, Dak’Art has established itself as one of the major meetings of contemporary creation on the continent. But it is not limited to official institutions. It overflows, it invades public space, it invests unexpected places – private houses, schools, workshops, independent galleries, beaches sometimes.

What attracts me is this organic dimension. Dak’Art is an artistic event, of course, but also a social, political, urban event. He questions the relationship between tradition and modernity, between local and global. He shows another look at Africa: a look that creates, criticizes, invites.

Photographing the Biennale would therefore be to document a moment of freedom and reinvention. But it would also be to accept the complexity, the abundance, the sometimes ambiguity of the works presented. It is not an “easy” event to photograph, because it does not give itself right away. It requires time, listening, an ability to be surprised.

A polyphonic visual narrative

My ambition would not be to produce a homogeneous series of images, but rather a polyphonic visual narrative, like an artistic travel diary. I would alternate between portraits of artists, street scenes, details of works, moments of life. I would seek to create correspondences between places, faces, creations. My common thread would be this unique energy that crosses Dakar during the Biennale: a tension between creative effervescence and beauty, between militant expression and artistic momentum. I would also be interested in how the city becomes an open-air gallery. The works exhibited in public space tell a different story than those presented in the galleries: they dialogue with the inhabitants, the vehicles, the decrepit walls. They are confronted with the ephemeral, with the real. It is these interactions that I would like to capture.

Conclusion: photographing art in motion

Photographing the Dakar Biennale would be, for me, a way of telling how art can reinvent a city, a society, a continent. It would be both an aesthetic and ethical challenge: how not to betray the works? How to restore their power without reducing them to simple visual objects? How to capture the silent speech they carry? I am not a professional photographer. But I believe that the image can be a tool for understanding, meeting, transmission. And as part of Dak’Art, this tool becomes a bridge between the imaginary. My role, behind the lens, would then be that of a smumer.

This article is part of the practical work carried out by students on the Master’s Degree in Travel Journalism at the School of Travel Journalism.